The Reindeer Have Landed

Farewell, Pandora

December 1, 2017

Zoo Update

December 1, 2017

Reindeer at the L.A. Zoo Photo by Jamie Pham

A herd of real reindeer has made the L.A. Zoo their home for the holidays once again, as part of Reindeer Romp, on now through January 7 (except December 25). Don’t miss your chance to see these animals up-close and learn about them from our expert reindeer keepers, who are giving special talks every day at 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. To prepare for your visit with these iconic caribou, read on for fascinating details on reindeer lore, biology, and history.

We Go Back. Waaaaaay Back

Anthropologists estimate that as long as 10,000 years ago humans began to tame the reindeer, and some of the oldest cave art in the world depicts these animals. During the Pleistocene epoch they crossed the land bridge across the Bering Strait from what is now Russia into North America, where they came to be called caribou. This name comes from the Native American Mi'kmaq (Micmac) people’s name for these animals: kaleboo, which means "pawer, scratcher," from the way that these deer kick snow aside to find lichens and mosses to eat during the winter.

Today, reindeer are still integral to various indigenous cultures from Scandinavia to the eastern fringes of Siberia still rely on reindeer. Like North American bison, they are migratory and play a vital role (similar to that of bison in Native American culture) in the traditional culture of the Laplanders (or Sami) of Scandinavia as well as the Native Americans of Alaska and the First Nations peoples of the Yukon, and Northwest Territories of Canada.

Well Equipped for the North Pole

Though they are closely related to the southern pudu, found in Argentina and Chile, and the tufted deer, native to Burma and China (both found at the Zoo), they have adapted to the harsher climate of northern latitudes.

The hairs that make up their thick coats are hollow, providing optimal insulation.

When the reindeer walk, their leg tendons make a clicking sound that biologists believe helps the animals stay together in snowstorms when they cannot see one another. Their hooves are specially adapted to provide traction in snow and ice and, although they are diminutive compared with other northern hemisphere species of deer such as elk and moose, they are sturdy enough to carry riders and pull sleighs—which is likely how they became part of the Santa Claus story.

Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, and Blitzen? Girls’ Names

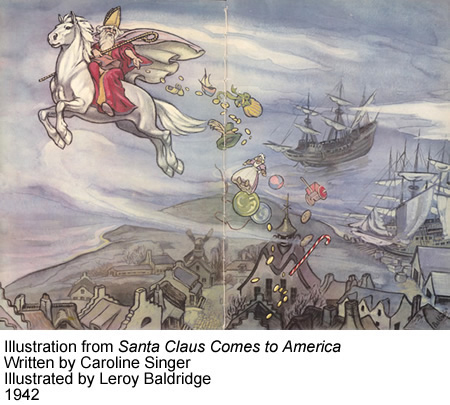

Originally, jolly old Saint Nick rode a white horse to deliver sweets to good children, but as his gift delivery responsibilities grew in the 20th century, he upgraded to the now-familiar sleigh pulled by eight tiny reindeer (nine if you count Rudolph). The only domesticated deer, reindeer pull sleighs and provide transportation. They are strong and can pull a 300-lb. load at 8 mph for 25-30 miles in severe winter conditions.

Both male and female reindeer grow antlers and shed them annually, but the males lose their antlers in the fall, after the breeding season (or “rut”) is over and they no longer need to defend their harems of five to 15 does from rivals. During the rut, males inflate the pouches of skin under their throats to amplify their mating calls and then bugle, snort, and rattle their antlers to attract females.

The females generally retain their antlers through the winter and into late spring to compete for food, dig up lichens to eat, and protect their young. Thus, Santa’s antler-sporting reindeer herd is made up of females.

Reindeer are considered the most highly evolved runners in the deer family and can achieve speeds of up to 30 mph for short distances. They may or may not actually fly, but they will effortlessly transport you and your family into the heart of the holiday season. Make a visit with them part of your Yuletide festivities.