New in the Zoo

Stand Up and Be Counted

January 7, 2020

From the Field: African Gray Parrot Rehabilitation

January 7, 2020

Gorilla Female N'djia Photo by Jamie Pham

In July 2018, the newest Campo Gorilla Reserve resident made her public debut: a 24-year-old female western lowland gorilla named N'djia transferred to L.A. Zoo from the San Diego Zoo as part of a Species Survival Plan (SSP) breeding recommendation to be paired with silverback Kelly. N'djia immediately started assimilating well with the Zoo's family group, which also includes Rapunzel and Evelyn, and Kelly took an immediate interest in her. N'djia was curious but cautious. Kelly showed great patience and gentleness with N'djia, an approach that worked! On November 21, 2019, the Los Angeles Zoo announced that N'djia is pregnant with her first baby. You are invited to follow us on this journey as we share a series of short videos discussing why this birth is so special for the Zoo and important for this critically endangered species. For the latest updates, see #LAZooGorillaBaby on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Our mild Mediterranean climate means that winters in Southern California might not be as extreme as other parts of the country, but it is cold enough for some of our native animals to chill out for the season. Last month, Trucker and Toko, the Zoo's resident California desert tortoises, moved to off-exhibit habitats where they are brumating—coping with cooler weather in a lowered metabolic state that conserves energy. Reptiles depend on the ambient temperature outside their bodies for energy. When it is too cold, they cannot properly digest food, so they have adapted to this by spending cold seasons in an "energy saver" mode akin to hibernation. Additionally, some of the smaller lizards you might usually see in the Arroyo Lagarto have moved to indoor habitats for the winter.

In the Australia section of the Zoo, the short-nosed echidnas began going into torpor—not true hibernation or brumation, but a similar state of temporarily lowered metabolism that is triggered by low temperatures. Hummingbirds and many other animals go into torpor to conserve energy in cooler weather. So if you don't see some of your favorites at the Zoo, they may just be waiting out winter in their off-exhibit quarters.

When evening approaches, hummingbirds look for perches where they can spend the night in a kind of temporary hibernation called "torpor" that conserves energy when temperatures drop. Because hummers require so much "fuel" for their daily activities, they cannot waste energy "idling." Photo by Lori Conley

On November 16, a female black duiker was born. As is customary with duikers, gerenuks, and deer, she will spend some time in the Winnick Family Children's Zoo nursery hoofstock yard, which helps the youngsters become accustomed to human sounds and activity. Although duikers may resemble tiny deer, they actually belong to the same family as cattle (Bovidae). Duiker calves at the Children's Zoo are bottle-fed whole cow's milk and begin transitioning to solid food at about two weeks of age.

Indian peafowl are among the world's most recognizable birds and they have naturalized in many places outside the Indian subcontinent. (Males are referred to as peacocks and the females are peahens—their offspring, as you might guess, are peachicks.) The conservation status of Indian peafowl as evaluated by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is "Least Concern." However, populations of the two other peafowl species are not so stable. Green peafowl (native to Southeast Asia) are "Endangered," and Congo peafowl (native to the Congo Basin) are "Vulnerable" with populations declining due primarily to habitat loss. So the hatching of a Congo peachick at the L.A. Zoo in November—the first since 1997—was cause for celebration. This hatchling is being cared for by the parents in the off-exhibit Avian Conservation Center.

Additional clutches of mimic poison frogs and splash-back poison frogs also hatched.

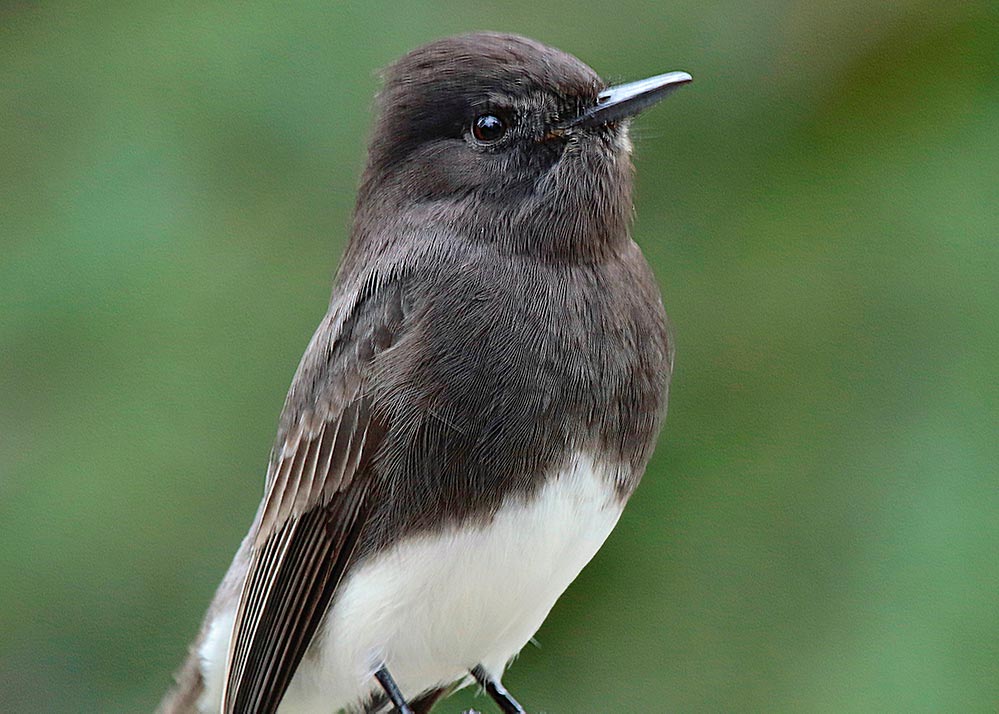

At the November 16 autumn members' bird walk, the group spotted 23 wild bird species: mourning dove, Anna's hummingbird, Allen's hummingbird, rufous hummingbird (a rarity), American white pelican (flock in a flyover), Cooper's hawk, acorn woodpecker, Nuttall's woodpecker, northern flicker (identified by sound), yellow-chevroned parakeet (same flock fly-over three times), black phoebe, common raven, bushtit, ruby-crowned kinglet, Bewick's wren, European starling, northern mockingbird, house finch, lesser goldfinch, dark-eyed junco, white-crowned sparrow, red-winged blackbird, Brewer's blackbird, and yellow-rumped warbler.

On November 19, about 50 students from Fillmore Middle School spent the day at Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge learning about conservation science and outdoor recreation as a part of the CondorKids curriculum they have been studying. The students took part in monitoring wild California condors, archery, hiking, and observing biologists—including L.A. Zoo Condor Keeper Debbie Sears—as they handled and examined the birds. Staff from the Santa Barbara Zoo, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-Ventura, and the Institute for Wildlife Studies were also on hand.

In other condor news, on November 23, CBS News covered the L.A. Zoo's successful participation in the California Condor Recovery Program. Since becoming a founding member of the program in the 1980s, the L.A. Zoo has been a leader in bringing this critically endangered bird back from the brink of extinction. In 2019, the Zoo debuted a new breeding technique that allowed a set of parent condors to rear two chicks at one time-a technique that no other institution had tried before. To see the full story, go here.